History of Nurse-Midwifery Program Reveals a Lasting Commitment to Community Care and Political Advocacy

(February 23, 2023) — In a July 1972 press release, School of Nursing Dean Sr. Rita Marie Bergeron announced the creation of a nine-month post-baccalaureate certificate program in nurse-midwifery education dedicated to improving the alarmingly high rate of infant mortality in Washington, D.C. Over the next two decades, the program would achieve remarkable success in providing perinatal care to the D.C. community and advocating for the profession of midwifery.

“Washington, D.C., ranks first in infant mortality rates for cities of its size and second only to Mississippi when considered a state,” said Bergeron.1

The nurse-midwifery program was the first of its kind in the D.C. area and one of just 10 similar programs in the country designed to prepare students to pass the certification requirements set by the American College of Nurse Midwives. Initial funding for the program was provided by the National Institutes of Health and the DC Department of Health.

Forty-four students applied to the first cohort of nurse-midwifery students and six were selected to complete the program. Students had to be registered nurses and have a bachelor’s degree to apply. Preference was given to applicants within the Washington metro area because graduates were required to commit to practice in the area as part of initial funding agreements with city agencies. In exchange, student nurse-midwives received tuition and a living stipend for themselves and their dependents while attending the program.2

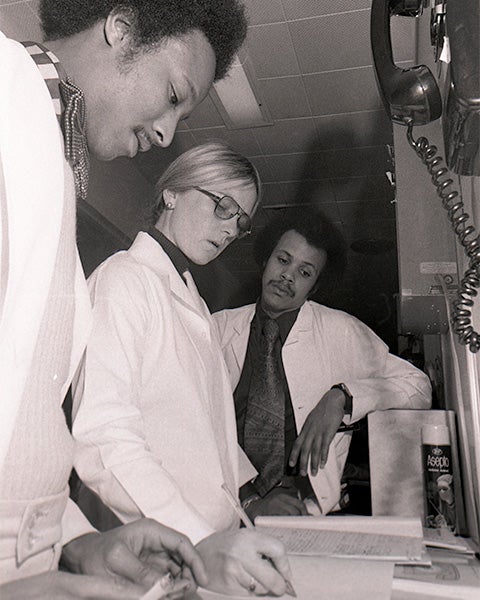

A faculty member demonstrates an exam technique, circa 1975. (Image: GU Archives)

The trailblazing program began at a time when some states still prohibited certified nurse-midwives from legally practicing. In 1971, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, The Nurses Association of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American College of Nurse-Midwives issued an important joint statement on maternity care that helped improve the status of the profession by recommending “qualified nurse-midwives assume responsibility for the complete care and management of uncomplicated maternity patients.”3

Within a year of the joint statement, which carved out a defined space for midwives as part of a health care team for pregnant people, the School of Nursing and School of Medicine faculty created the nurse-midwifery program at Georgetown.

“I endorse the establishment of an education program of nurse-midwifery and assure you the cooperation of the School of Medicine in this program,” wrote John C. Rose, MD, dean of Georgetown University School of Medicine, in October 1971.4

Faculty secured the DC General Hospital as the principal clinical agency for the program, providing students experience in ambulatory care, labor and delivery, as well as postpartum and nursery care.5 Although the midwifery faculty continuously lobbied for access to Georgetown University Hospital, School of Medicine faculty remained reluctant to allow midwifery faculty and students access out of a concern for the small volume of deliveries available to a large number of staff. In 1980, for example, there were 208 third-year medical students with a required rotation in obstetrics/gynecology, 32 residents, and two fellows.6

Early Cohorts

The first group of six nurse-midwifery students completed their studies in October 1974. The chancellor of the medical center conferred their certificates, and four of the graduates went on to receive their American College of Nurse Midwives certification (ACNM) and were employed as nurse-midwives in the D.C. area.

A patient exam demonstration, circa 1975 (Image: GU Archives)

From the beginning, the faculty intentionally recruited African American nurse-midwives to teach in the program, with 10% of the student population identifying as Black. Additionally, the student midwives entered the program as established working medical professionals: Thirty percent of students had a master’s degree; 76% had at least four years of work experience as a registered nurse; and the median age of students was 32.7

The vast majority of admitted students were female, but possibly the first male midwifery student in the country, Ira Yedlin, was admitted with the Class of ’77 cohort. Yedlin went on to practice as a midwife at a birth center in Seattle, Washington. After completing his studies at Georgetown, Yedlin delivered his own son. Shortly after the birth, his wife told a reporter, “most husbands are left in the dark about pregnancy, but Ira knows more than I do about it.”8

After receiving their certification, over 75% of these early graduates went on to practice as nurse-midwives, with approximately a third of graduates each working in rural, suburban and urban settings. In addition to going on staff as nurse-midwives in hospitals and community clinics, graduates also established their own practices across the country, from California to Massachusetts. Some graduates even joined the nursing faculty at Georgetown and other universities.9

Mary Ann Johansen (NM ’76) captured the energy the early graduates had for their chosen profession in her 1976 Commencement speech at Georgetown. “The nine months we are here are analogous to the pregnancies of our patients,” she said. “We had an initial period of adjustment to change that was characterized by uncertainty and fatigue. As we gained knowledge and skills, and established relationships with our patients, we accepted the task at hand. Our tasks are formidable, whether we be in the municipal hospital, the rural clinic, the suburban office or the home. But our heritage as nurse-midwives is to be change agents. Let us begin!”10

Building a Lasting Program

Yuen Chou Liu, PhD, CNM (Image: GU Archives)

After considering several candidates, leadership from the School of Nursing and School of Medicine named Yuen Chou Liu, PhD, CNM, as the program’s first director. Liu received her CNM certification at the Booth Maternity Center in Philadelphia and delivered over 300 babies herself before becoming program director.

“Above all, the human dignity of the mother must be respected,” Liu said in an interview about her new appointment. “She is the one having the baby and not the professional.”

The autonomy of the pregnant person in making health decisions, especially during labor and delivery, was a pillar of Liu’s vision of a midwifery education.11

After the second cohort of students graduated in 1975, Liu stepped down as program director and assumed a professorship in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Georgetown’s School of Medicine, where she pursued research on maternal and child health.

The same year Liu departed, Georgetown hired Judy Melson, CNM, as a faculty member. She would spend the next 15 years of her life leading the program through a series of changes and challenges to the profession of midwifery.

From 1974-1980, the certificate program graduated 60 students, 44 of whom became certified nurse-midwives. During this period, nurse-midwifery faculty and students delivered over 1,300 babies and educated over 300 couples through childbirth education at DC General Hospital. The nurse-midwifery program also fought to allow fathers and other family members to attend births. In 1975, only one hospital in the D.C. area allowed relatives to be present. By the 1980s, the practice was widespread, in large part due to the influence of Georgetown’s nurse-midwifery program.12

In 1980, during Melson’s first year as program director, the nurse-midwifery program evolved from a nine-month post-baccalaureate certificate to a 16-month master’s degree program.

Graduates of the newly formed master’s program were required to attend at least 20 births before graduation.

“They will learn how to be 100% sure of the fetus position before birth and an absolute expert in distinguishing normal from abnormal cases,” said Melson in a May 1981 Georgetowner Community News article.13

Community Focused

In November 1982, the midwifery program received a three-year, $124,000 grant from the Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. Foundation to place certified midwives in D.C. health department clinics in low-income areas to improve the stubbornly high infant mortality rate. The program specifically serviced pregnant people and their families under the age of 20. The midwives provided 24-hour coverage for labor and delivery at DC General Hospital, a team of midwives so dedicated to keeping their patients on track that they would try to find adolescents who missed appointments, and teach classes focused on labor and delivery as well as infant care, nutrition and family planning.14

The midwives operated out of Hunt Place Clinic in Ward 7 and Adams Morgan Clinic in Ward 1. At the time, a quarter of the city’s public-assisted housing was located in Ward 7 and patients at the clinic were primarily low-income and African American. The average age of patients at the clinic was 17 years old, but midwives saw patients as young as 13. The Adams Morgan Clinic was located in the heart of the Latino community in Ward I, and the clinic saw primarily refugees from El Salvador, in which the highest average level of education completed was seventh grade. The midwifery program strove to always staff the Adams Morgan clinic with a Spanish-speaking CNM so that the midwife could communicate directly with patients.15

In 1986, Eunice Kennedy Shriver wrote to the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health in support of Georgetown’s midwifery program. (Image: Wikipedia)

To raise awareness of the program, Georgetown nurse-midwives contacted school nurses at local high schools and middle schools and participated in local radio and television programs, including several bilingual programs.

The program was renewed for several years after the initial grant. A 1987 report on newborn outcomes for clinic patients showcased the success of the midwives’ efforts. For the 418 adolescents who delivered with the program, the neonatal mortality rate was 7.2/1,000; the rate in D.C. at the time was 15.9/1,000.16

“Over the past four years, the School of Nursing midwifery graduate program has established and administered services at two health centers in the city,” wrote Eunice Kennedy Shriver in a letter to the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health in October 1986. “The results of these efforts have demonstrated a decrease in all negative prenatal indices for the population served. These positive results have saved the taxpayers an estimated $800,000 in curative service costs.”17

Ward 3 Rep. Polly Shackleton also wrote to the human services committee in D.C. in support of the program. “With its unique emphasis on frequent prenatal and postpartum visits, prompt follow-up for missed appointments, health promotion and nutrition and personalized education, I am convinced this program is precisely what the district needs if we are to make lasting progress in lowering the rates of infant mortality and morbidity in our city,” she wrote.18

In 1989, the program relocated out of the city clinics and found its new home in Mary’s Center, a then-newly created community health clinic founded by School of Nursing alumna Maria Gomez (NHS’77).19

Acting as Advocates

Despite the early successes of the nurse-midwifery program, Georgetown faculty were repeatedly pulled away from their academic duties to advocate on behalf of their profession, which faced continual political attacks throughout the 1980s.

Midwifery faculty members were repeatedly called on to advocate for their profession. (Image: GU Archives)

In April 1983, Melson testified to the New Jersey Board of Medical Examiners in opposition to proposed regulations requiring nurse-midwives be supervised by an OB-GYN. “The requirements for direct supervision in the proposed rules are presumptuous, professionally inappropriate, and unfairly restrictive of nurse-midwifery practice,” she said.20

Throughout the 1980s, states and localities, including D.C., debated licensing requirements for midwives as well as regulations deciding whether midwifery care would be covered by health insurers. Georgetown midwifery faculty members Sally Austen Tom, CNM, and Deborah Bash, CNM, testified on Capitol Hill about nurse-midwives being denied hospital privileges after the issue garnered national attention.21

In March 1981, midwives throughout the D.C. area also organized a screening for members of Congress at the British Embassy of the documentary “Daughters of Our Time,” which tracked the work of three practicing nurse-midwives, including Marion McCartney, a 1974 graduate of Georgetown’s nurse-midwifery program. A young Tennessee congressman named Al Gore spoke out at the time in support of the nurse-midwives’ lobbying efforts and told a reporter in 1981 that “[pregnant] patients should be able to exercise freedom of choice without restraint or intimidation.”22

In the mid-1980s, Georgetown’s nurse-midwifery faculty successfully lobbied for legislation in D.C. that prohibited district hospitals from engaging in discriminatory practices to limit hospital privileges for delivery to physicians. Following this new law, nurse-midwifery faculty created their own midwifery practice, Georgetown Midwifery Associates (GMA) in 1986. GMA was headquartered at the School of Nursing and sought to meet the demand for private, hospital-based nurse-midwifery care in the D.C. area. GMA routinely handled 10 to 15 patients per month for prenatal care and delivery, as well as seeing clients for gynecological and family planning services.23

Local medical professionals acknowledged the nurse-midwifery program’s positive impact on the health of pregnant people and their families. This sentiment was captured in a 1982 letter to the program from Annelies S. Zachary, MD, MPH, chief of maternal health and family planning for the Maryland Department of Health. “I had the opportunity to meet several graduates of the Georgetown nurse-midwifery program in maternity clinics at our local health departments. Graduates of Georgetown have exhibited a high degree of practical and scholastic expertise. They are well-trained in patient education and community health. Their contribution to maternity and well-women reproductive care has made a remarkable impact in the perinatal health care for women.”24

Heather Wilpone-Welborn

GUMC Communications

Top Image: The first class of students in the School of Nursing’s post-baccalaureate certificate program in nurse-midwifery education graduated in 1974. (Image: GU Archives)