School of Nursing Commencement Speaker Says Every Patient Interaction is ‘Sacred’

(May 6, 2024) — The School of Nursing Class of 2024 enters a health care landscape in this country where health care disparities continue to be as significant as they’ve ever been. The COVID-19 pandemic did not create these disparities but it certainly exposed them, according to Patricia “Tish” Polgar-Bailey, FNP, MPH, PsyD, a family nurse practitioner and clinical psychologist at the Charlottesville Free Clinic in Virginia, who will address the nursing school graduates at their 2024 Commencement on May 17.

Patricia “Tish” Polgar-Bailey

Despite the changes in the health care system, it remains critical for health care providers to cultivate the art of listening, which Polgar-Bailey has personally worked to improve. Admitting that she has been tempted to order additional tests or draw more labs when stumped by a patient, over her years of experience she has learned that listening is the best thing to do.

“The answer often is not in those diagnostic tests, but in something else that the patient has or hasn’t said yet at that point,” she said. “But if you open up the space to listen, sometimes what you’re looking for, the information that you need will come.”

The Girl on the Canal

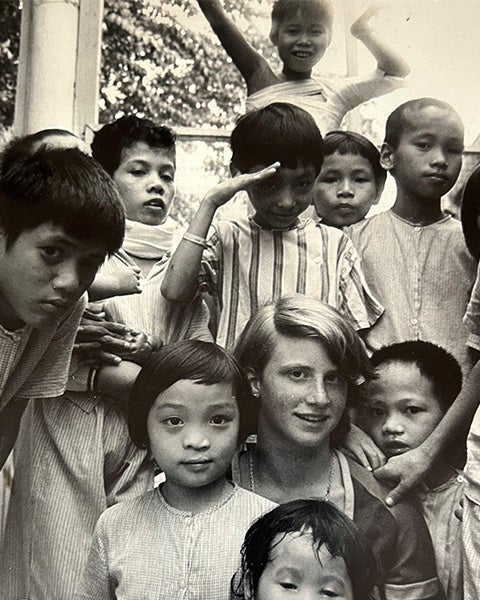

The pandemic shed light on health disparities, but Polgar-Bailey first recognized social inequality as the daughter of a diplomat attending high school in Bangkok. “Like most big cities,” she said, “you see the disparities in the way people live, so there’s very wealthy parts of Bangkok, and then there are parts of Bangkok that are incredibly poor.”

Polgar-Bailey spent her school vacations working at an orphanage and rehab center for children in Vietnam, another formative experience that she says sparked her interest in nursing as a career.

One day, as she wandered along one of the city’s many khlongs, or canals, she saw a Thai girl around her own age about 10 feet away on the other side, washing her family’s clothes in the polluted water. “She looked up just as I was looking at her and we smiled at each other,” recalled Polgar-Bailey, “and I was aware at that point of my relative privilege in life … and it made me think, ‘Why is she on that side of the khlong and I’m on this side of the khlong, and why are our lives so comparatively different?’ And I also realized in that moment that we were alike — two girls trying to make our way in the world.”

“I still remember exactly what she looked like,” Polgar-Bailey added. “And her face, that image and that experience have always stayed with me. I feel like she’s always been with me, accompanying me. I’ve sort of taken her with me the rest of my life. And at that moment, I was convinced that I needed to use the resources that I had to help people who don’t have lives that are as comfortable as mine.”

From then on, she knew that she wanted to help improve the lives of people from underserved and marginalized populations. “It felt like more of a calling that I was compelled to respond to than a decision that I was actually making,” she said.

Striving to ‘Change the Ending’

After high school, Polgar-Bailey studied economics and anthropology as an undergraduate at the University of Virginia before going to nursing school and later adding a master’s in public health, then a doctorate in clinical psychology.

For those about to embark on their careers in health care, Polgar-Bailey stressed the importance of working for an institution whose values are consistent with their own. Finding that fit might mean a smaller paycheck, but the payoff will be in lower stress and greater personal and professional satisfaction.

“That’s one of the things that I appreciate about working at the Charlottesville Free Clinic,” she said. “We don’t bill because our patients don’t have insurance. … We can see people as often as we need to. We’re not limited by what the billing code tells us is an appropriate number of visits, or at least a reimbursable number of visits. There’s not the emphasis to see more and more patients.”

Working at the free clinic gives Polgar-Bailey time to look at patients more holistically to gauge what factors may be contributing to that problem, or if there might even be a more important issue. “One of the things that I’ve learned over the years is that every experience with a patient is really sacred,” she said. “And I don’t mean that necessarily in the religious sense. … I mean it more in the transformative sense.

“Even if a person comes in for something that seems to be relatively straightforward and easily fixed, there’s power in that experience,” Polgar-Bailey added. “And at least for the populations that I work with, that are more marginalized and underserved, often they have never had an experience where they have felt respected and cared about and treated with the dignity that’s inherent in every human being.”

How a nurse or doctor behaves with a patient in that moment, however brief or long, can be more transformative than the treatment for the health issue involved. One experience of being truly listened to and cared about may give a person hope that their life can be different.

Polgar-Bailey treasures a quote sometimes attributed to C.S. Lewis, among others: “You can’t go back and change the beginning, but you can start where you are and change the ending.”

“I can’t change the very difficult beginnings and trauma that many of the patients I see have experienced or fix all of their problems,” she said. “But I can meet them where they are and provide what I can to help them write a different ‘rest of the story.’ I can provide an experience in which they know they matter, that they are respected and heard and cared about.”

Michael von Glahn

GUMC Communications