‘Awarded a Place’ – Nursing Students in the College of Arts and Sciences

March 19, 2020 – For many years, nursing alumna HelenMarie Dolton (BSN 1953) has kept letters related to her admission to the university in a scrapbook with the cover message, “My Years at Georgetown.”

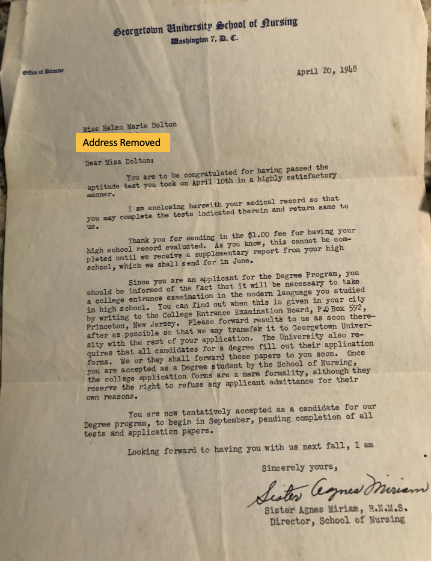

One of them – an April 20, 1948 letter from Sister Agnes Miriam, of the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth (SCN) and director of the School of Nursing – praised Dolton for her success on testing, shared other instructions, and offered tentative admission “pending completion of all tests and application papers.”

Sister Agnes Miriam counseled, “The University also requires that all candidates for a degree fill out their application forms. . . . Once you are accepted as a Degree student by the School of Nursing, the college application forms are a mere formality, although they reserve the right to refuse any applicant admittance for their own reasons.”

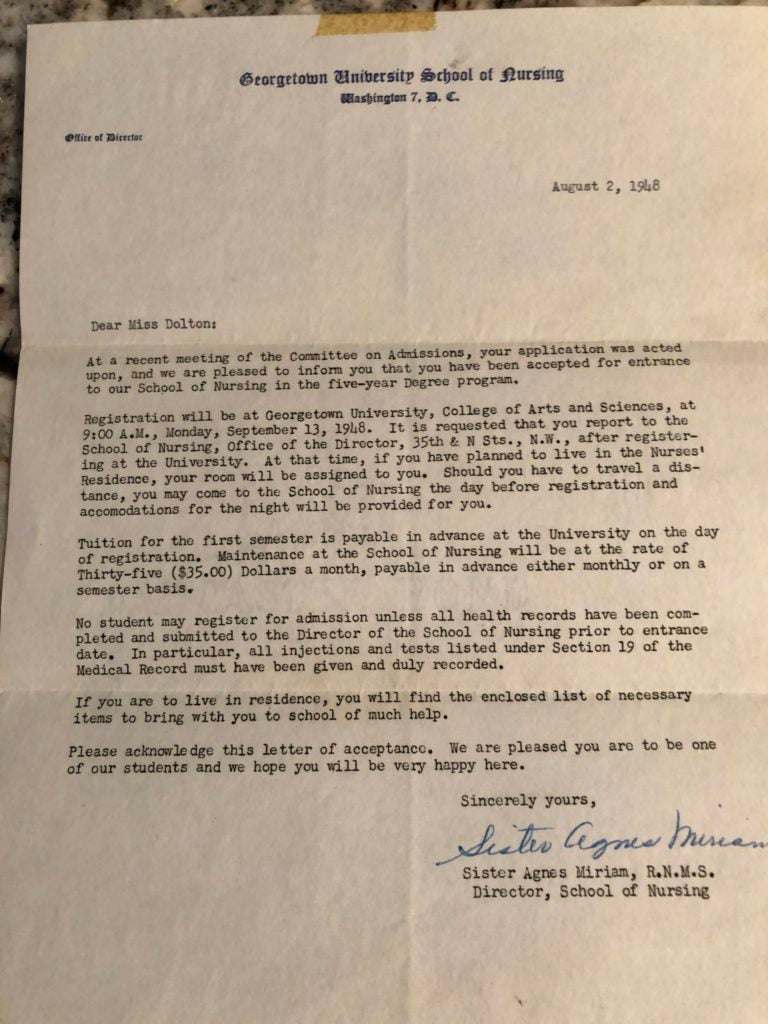

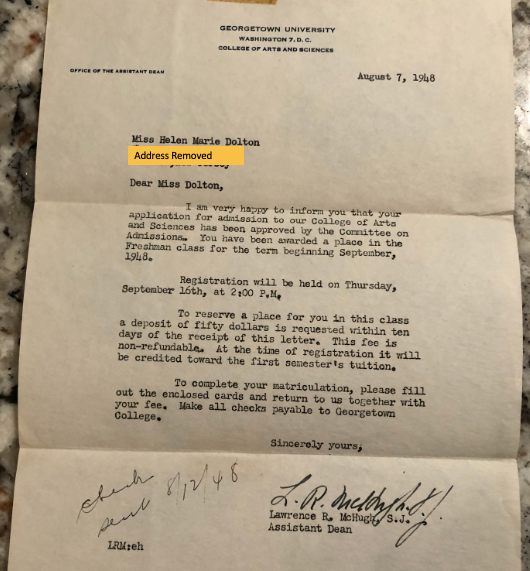

Then in August, the good news finally arrived. Sister Agnes Miriam mailed Dolton a letter accepting her to the nursing school. And five days later, the Rev. Lawrence R. McHugh, SJ, an assistant dean in the College, sent another admitting her to the College.

He wrote to the high school graduate from New Jersey, “I am very happy to inform you that your application for admission to our College of Arts and Sciences has been approved by the Committee on Admissions. You have been awarded a place in the Freshman class for the term beginning September, 1948.”

As the College of Arts and Sciences (now known as Georgetown College) celebrates its truly exciting and historic 50th anniversary of officially admitting women across its academic programs, Father McHugh’s letter to Dolton, along with other archival materials and historical memories, sheds a bit of new light on the presence of women, through the nursing program, in the College in the 1940s and 1950s.

Women in the College: Pre-1969

Back then, Dolton took part in what was called the five-year bachelor’s program in nursing. The three years of education in the School of Nursing followed an initial two years of study in the College.

What piqued the curiosity of the School of Nursing & Health Studies and the University Archives was the fact that Dolton had been admitted to the College in 1948 in addition to the School of Nursing. It has been reported in various sources about five-year nursing students taking College classes in this era.

But the admissions to the College part seems much less so.

McHugh’s correspondence added, “To complete your matriculation, please fill out the enclosed cards and return to us together with your fee. Make all checks payable to Georgetown College.” A handwritten note in the letter’s margin indicated Dolton’s $50 check was mailed on August 12.

Twenty years before the historic 1968 decision to officially make the College of Arts and Sciences a coeducational school – as saved letters from long ago suggest – women had been apparently admitted to the College, at least through one educational program.

Making Sense of the Pieces

With these interesting pieces of history, the School of Nursing & Health Studies and the University Archives collectively brainstormed sources of information. A review of some records from Georgetown’s collections added interesting detail.

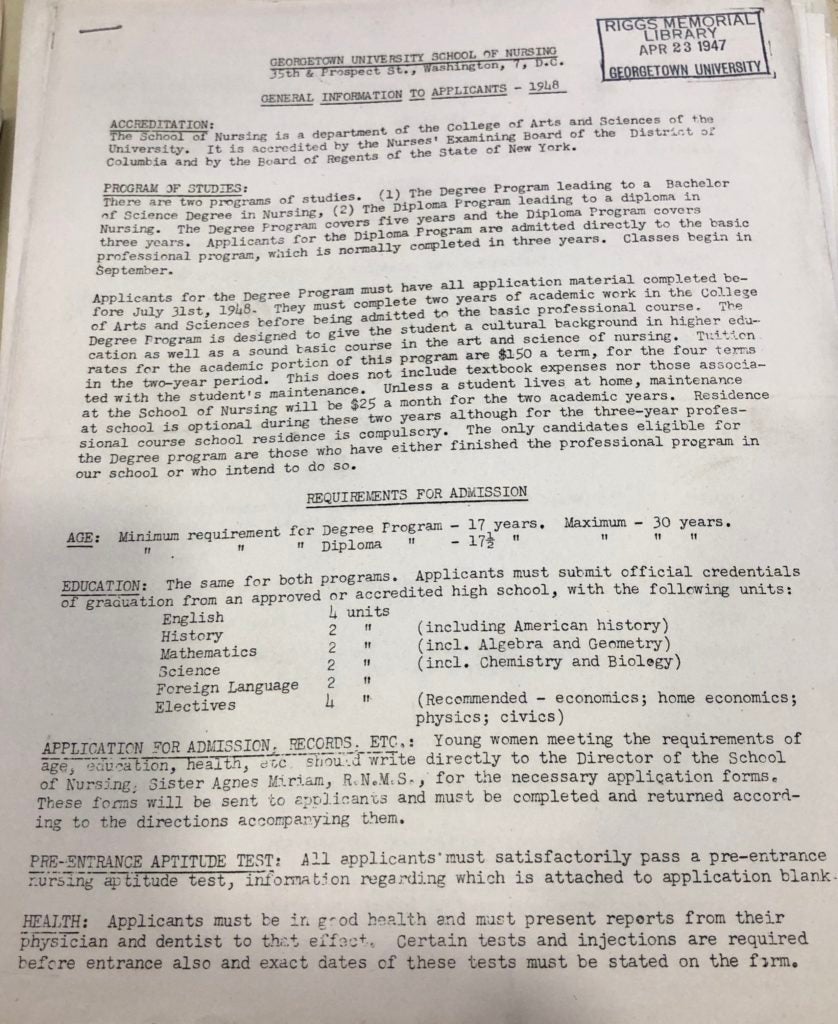

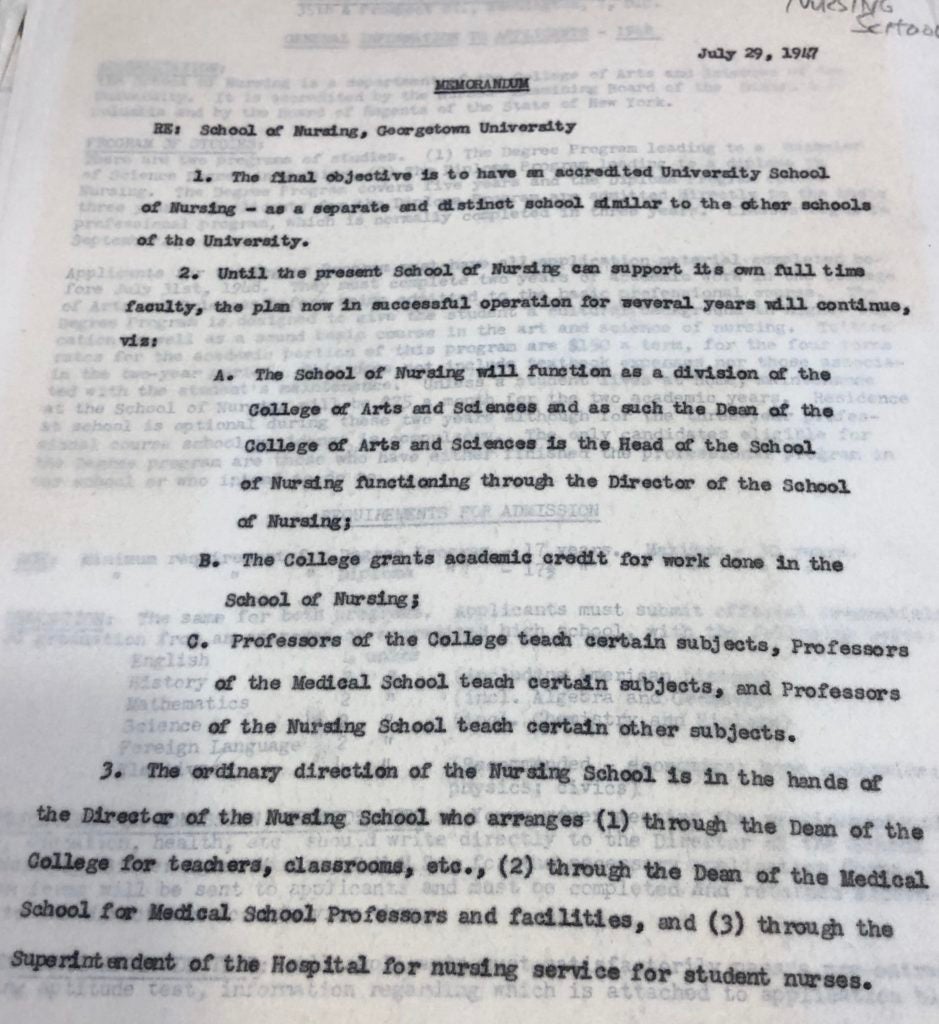

The first page of a School of Nursing information sheet, date stamped April 23, 1947, described the application process for individuals interested in beginning in 1948. (Photo of document housed in the Georgetown University Archives.)

For example, published registries from this period included the five-year BSN enrollees as registered College students during the foundational two years. A check of a few BSN graduates showed a “C” listed by their names in the College years and an “N” listed in the subsequent nursing years. The 1948-1949 book read, “The letter indicates the department in which the student is registered . . . .”

(One registry is missing between 1947-1952 covering academic year 1949-1950.)

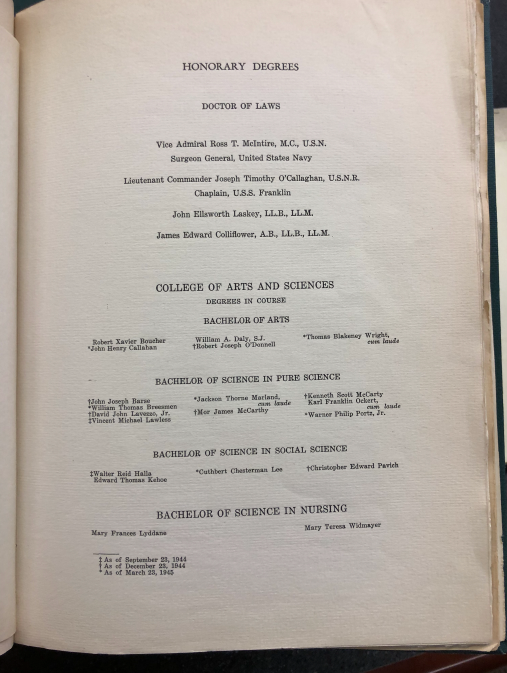

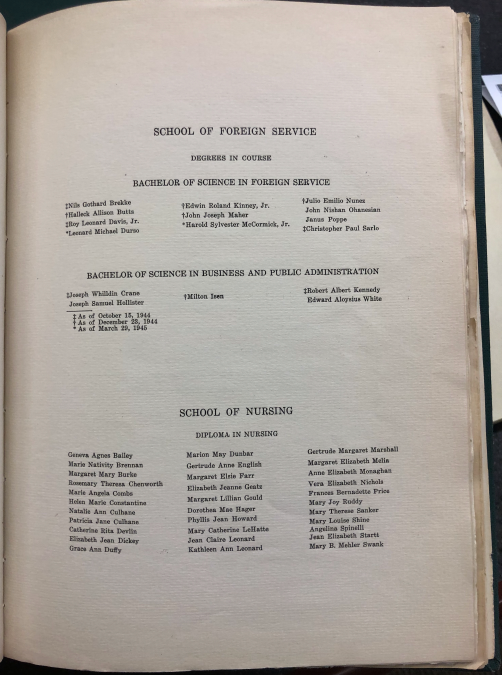

And in the 1945-1948 Commencement programs, BSN graduates were printed under the College versus the School of Nursing, which was placed elsewhere in the printed booklets and included the three-year diploma graduates. Beginning in 1949, the BSN grads were printed under the School of Nursing.

The ‘Extension’ Model

Previous histories and archival documents give context about campus and why this might have been occurring back then.

In the late 1930s and 1940s, according to Dr. Alma S. Woolley’s 2001 history of the nursing school and other records, Georgetown conceptualized and offered collegiate “extension courses” for women who held a nursing diploma to earn the baccalaureate degree. (They were known then as “graduate nurses.”)

Woolley referenced a September 23, 1938 letter from the Rev. John E. Grattan, SJ, dean of the College, to the Georgetown president, who was addressed then as, “Reverend and dear Father Rector.” Father Grattan had in 1936 expressed reservation about the BSN degree itself and pondered a change to tradition in terms of women earning undergraduate degrees at Georgetown.

A copy of the 1938 letter, housed in the Georgetown University Archives, laid out a working plan for the new initiative and posed a series of questions, such as who would be responsible for administration, “the College, the University, or the School of Nursing in conjunction with the College,” and could priests, in addition to lay College faculty, teach classes.

Father Grattan wrote, “Since thirty graduate nurses have signified their interest in such courses, it is proposed to offer five courses this year.” Cultural and religious coursework would be among the topics covered.

“It is proposed,” he added in the two-page document, “to limit enrollment in these courses to nurses who are graduates of the Georgetown School of Nursing, or graduates of other schools who are now in the employ of the Georgetown University Hospital. We would not allow outsiders to register for these courses.”

Don’t Mention It

Nearly four years later, on July 14, 1942, Father Grattan wrote to the Rev. Stephen F. McNamee, SJ, his successor as the College’s dean, and explained the situation with the extension courses, which were being “conducted in the Georgetown Hospital for the benefit of the graduate nurses as well as for the Sisters of St. Francis.”

Grattan admitted to McNamee that he and the registrar, Dr. Walter J. O’Connor, found this endeavor unproductive, but wanted “to fulfill our moral obligation to certain graduate nurses who have taken the majority of their work towards a degree.”

He indicated the most recent students would participate in the October 1943 graduation ceremony.

This detail might help explain an entry in a 1957 alumni directory highlighting three women with the BSN degree under the year 1943. They had previously received the three-year diploma in nursing at Georgetown, according to the directory itself and the added help of a May 28, 1937 Washington Post article.

Perhaps reflecting his concern about women on the campus, Father Grattan advised Father McNamee in 1942 about the extension students, “On October 7th the same students will begin Zoology under Father Coniff, and in February, Botany. They will attend both lectures and labs in the Biology Bldg. The flutter over ladies on the campus will not be of long duration, and I suggest that no notice of their presence appear in ‘The Hoya’ or be given any publicity.”

‘Worthy Pioneers’

Also in the 1930s and 1940s, as sources indicated, Georgetown researched and offered a college-based, five-year program for nursing education, like the one that Dolton, the nursing alumna from 1953, and her contemporaries completed.

Documents from these decades, according to Woolley and archival sources, presented a vision for a five-year program with the collegiate coursework being offered at Georgetown Visitation Junior College since, as one said, “the College of Arts and Sciences is not co-educational.” Georgetown President Arthur A. O’Leary, SJ, reinforced a similar message to the Jesuit provincial in his October 7, 1939 letter.

A document attached to O’Leary’s letter stated the option would launch in September of 1940. That start date, reported in sources like Woolley, remains murky, as does with whom and the location where the women would take their college classes.

For instance, an unsigned memo to the university’s president – typed on College dean’s office letterhead and dated September 8, 1943 – summarized the point of view of Sister Joanilla, OSF, who led the nursing school. She wanted her students who had been applying for the baccalaureate option “to attend regular college classes until the number reaches 10 or so when separate classes would be established for the girls.” The unnamed writer, perhaps Father McNamee himself, agreed.

“I think that the boys would receive the four or five nurses well and would understand that it is a temporary measure,” the unknown memo author surmised. “Hence I suggest that Sr. [Joanilla] be allowed to canvas the girls at present enrolled and announce that they might begin the course NOW.” (Woolley also cited this memo, which was entitled, “Concerning the Collegiate Nursing School of Georgetown University,” and she put forth that this request was not put into effect.)

So by late summer 1943, it appears as though an option was up and running for enrolled nursing students at the hospital diploma program with the idea that courses might be taught on campus. (This, of course, sounds similar to the extension model.)

Yet in April 1944, O’Connor, the registrar, responded to an inquiry saying the five-year BSN was not yet ready for primetime. And just four months later, on August 25, 1944, Father McNamee, the College’s dean, wrote with excitement to the District of Columbia’s Nurses’ Examining Board.

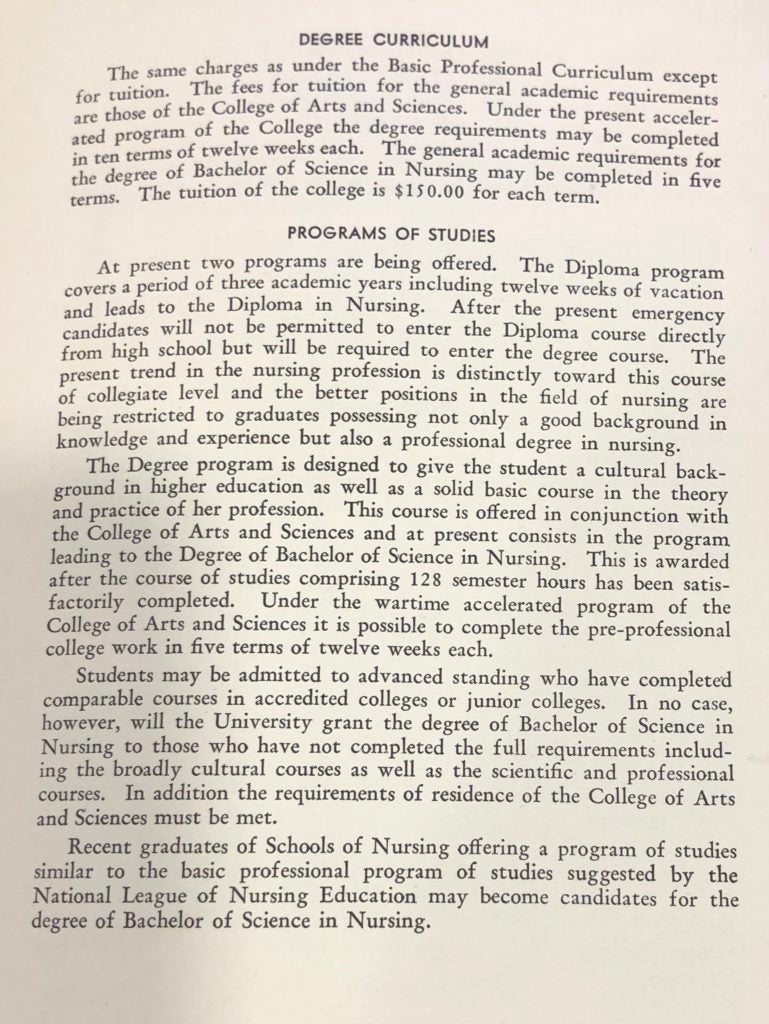

“I am sure that you will be pleased to know that the two nursing programs now being offered by the School of Nursing of Georgetown University are under the direction of the College of Arts And [sic] Sciences,” he wrote. “You will be the first office to receive a copy of the announcement when it returns from the printer.” Indeed, an archived copy of the 1944-1945 brochure – maybe the one that Father McNamee referenced – listed both the diploma and the degree options.

Two days after New Year’s Day 1945, an enthusiastic Father McNamee wrote to the Rev. Mother Veronica, OSF, the superior general of the Convent of Our Lady of the Angels in Glen Riddle, Pennsylvania, with “the grades for the Sisters who are in the B.S. in Nursing Program in the College of Arts and Sciences.” He was impressed by their academic commitment, said he would be teaching them epistemology, and called them “worthy pioneers.”

1945 to Early 1950s

So between the extension course model and the evolution of the five-year BSN program – one which, according to Woolley, enrolled its last students in 1950 to make way for the forthcoming four-year program – a possible explanation emerges about the women who were listed in the 1945-1947 Commencement programs.

Various archival records show that the women baccalaureate graduates of 1945, 1946, and 1947 were either members of the Sisters of Saint Francis or had previously earned a diploma in nursing at Georgetown’s hospital.

The three religious sisters from 1946 and 1947 were all, among other sisters of the congregation, included on an undated roster in the Archives entitled, “List of Sisters Attending Collegiate School of Nursing.” And the two women from 1945 had received their Georgetown nursing diplomas in 1941 and 1943, according to the 1957 alumni directory.

A program brochure from 1944-1945, housed in the Georgetown University Archives, described the baccalaureate option, including various ways to enter for prospective students.

With respect to the two 1948 BSN graduates, it appears, from an archived letter, that they had completed the required college coursework elsewhere prior to becoming students in Georgetown’s three-year diploma in nursing program. The 1944-1945 program brochure permitted such “advanced standing” for previous college credits, as well as the option for diploma nurses to enroll as collegiate students.

And in some of the years that followed, according to a review of the 1957 alumni directory and Commencement programs, the BSN graduates included a member of the Sisters of Saint Francis and many women who had earlier completed the diploma program on campus. So perhaps they, too, did the extension model or the five-year program in reverse, that is the School of Nursing years and then the College part.

A Close Relationship

The 1940s and early 1950s, according to Woolley and other materials, were a time of change for the School of Nursing, including a movement favoring degrees instead of diplomas, a greater alignment as a unit of the College, transitions in religious leadership at the hospital and the nursing school, and, ultimately, a more independent structure for the school itself. (Father McNamee, as Woolley wrote, was very involved in advocating for nursing and the collegiate model’s development.)

Additionally, the director of the school, Woolley reported, finally received the dean title in winter 1949. This occurred during the term of Sister Agnes Miriam, who signed, still as “director,” Dolton’s letters in 1948.

Within this timeframe, the College and the School of Nursing had a much more formal and intertwined administrative relationship, one that may also help clarify why baccalaureate-seeking nursing students were admitted to the College and listed as students and graduates of this much older campus unit.

For example, on May 21, 1945, Father McNamee, in his capacity as the College dean, wrote to the Georgetown president supporting optimized hospital space for the nursing school’s director Anne Murphy.

In addition, the Georgetown Archives contains a School of Nursing information sheet, date-stamped April 23, 1947, for applicants applying in 1948. This happened to be the year Dolton, as a high schooler, applied to Georgetown.

The document offered a description of the relationship between the two units: “The School of Nursing is a department of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University. . . . [Students] must complete two years of academic work in the College of Arts and Sciences before being admitted to the basic professional course.” (The earlier brochure from 1944-1945 used this language, “This course is offered in conjunction with the College of Arts and Sciences . . . .”)

The two-pager advised prospective students to contact Sister Agnes Miriam, although Dolton’s preserved letters revealed that the School of Nursing and the College administered their respective admissions processes and decisions.

A photo of a July 29, 1947 memo, housed in the Georgetown University Archives, described the relationship at that moment in time between the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Nursing. School historian Dr. Alma Woolley covered this memorandum.

Related to organizational structure, a July 29, 1947 memo, one which Woolley cited, also gave a pretty complete picture of the hierarchical relationship between the two units at this moment in Georgetown’s history. Some highlights from the document itself:

- “The final objective is to have an accredited University School of Nursing – as a separate and distinct school similar to the other schools of the University.”

- As it had for a number of years and until it could “support its own full time faculty,” the school would “function as a division of the College of Arts and Sciences and as such the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences is the Head of the School of Nursing functioning through the Director of the School of Nursing.”

- Professors from the College, the School of Medicine, and the School of Nursing would teach classes.

- The College gave “academic credit for work done in the School of Nursing.”

After this point, in the final years of the 1940s and the early years of the 1950s, depending on the source, the School of Nursing did achieve a more independent status on Georgetown’s campus.

Woolley’s book, drawing on materials from the 1950s and 1960s, reported that this happened in 1951. An earlier archived letter from August 26, 1948 told a slightly different story. In it, President Lawrence C. Gorman, SJ, wrote to the executive secretary of the District’s Nurses’ Examining Board on the topic of the Rev. Edward B. Bunn, SJ, becoming regent. He declared, “I think this will clarify the status of the School of Nursing as an independent School of the University.”

This incremental administrative shifting might assist in explaining why, beginning in 1949, the BSN graduates were listed under the School of Nursing in the Commencement program as opposed to the way they had been previously listed under the College of Arts and Sciences.

Unresolved Matters

Certainly, a much more thorough review of original and secondary sources is needed to understand the soundness of these initial observations and how this material and other evidence add to the narrative about women students in the College of Arts and Sciences – in the years before their admission for the fall of 1969. More work remains.

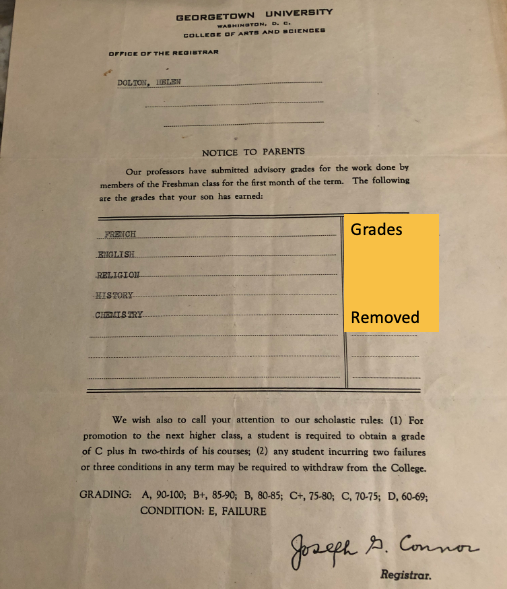

Dolton saved a copy of this advisory grades form her parents received after one month of coursework in the College of Arts and Sciences in 1948. (Photo of original document courtesy Dolton.)

Classes with men?

One area where additional work could be done involves understanding more about how women and men took classes together in the 1940s and 1950s.

This is a phenomenon, depending on the year and the model of the nursing program, that graduates have different memories of, according to a couple recent conversations with graduates and Woolley’s oral history archive. So there does not seem to be a general “yes or no” answer to this complex question.

The matter about whether there could be co-ed classes with the College, according to accounts in Woolley’s book, persisted in the years that followed.

For example, she quoted a 1954 report by the DC Nurses’ Examining Board, which stated, “‘Graduate nurses in the supplemental program [that is, a program that came after the extension course format that also allowed RNs to take courses to receive the BSN] have classes with other university students.’”

Woolley summarized details of a March 26, 1956 meeting: “The [nursing] executive faculty discussed the question of nurses sharing classes with men. Father [Joseph] Sellinger, dean of the college, stated that the present policy had not originated in the university, but that it was a Jesuit rule that could only be revoked by the Society of Jesus.”

In Woolley’s account of her oral history with Sister Kathleen Mary Bohan, SCN, the nursing dean from 1958-1963 admitted she and Father Sellinger allowed nursing majors to take classes with College students, something Father Bunn, the president, apparently discovered, with surprise, through a news article.

Lastly, a September 29, 1960 Hoya editorial, titled “Togetherness,” proclaimed, “A major change greeted hilltop upperclassmen on their return to school last Thursday. For the first time juniors from the Nursing School had been admitted to elective courses within the College and Foreign Service School, and their smiling faces were evident from Accounting to American Lit.”

A thorough investigation might provide a more concrete answer to this question.

Women in College culture?

A related area involves: How much did the College’s culture accommodate registered female students?

For example, on February 1, 1949, Father Coolahan, then the College’s dean, distributed an all-caps student notification, apparently geared toward male students.

Item seven, about a dress code, announced, “Attention is once again called to the matter of proper dress. In classrooms, laboratories, in chapel and dining room, proper dress includes collar, tie, and coat. Sweaters without coat, lumber jackets, windbreakers, etc…are not considered proper attire for students of the College of Arts and Sciences.”

In addition, during Dolton’s first semester in 1948, her parents received an advisory grades report, on College of Arts and Sciences stationery, that she has saved. It read, “Our professors have submitted advisory grades for the work done by members of the Freshman class for the first month of the term. The following are the grades that your son has earned . . . ” Boldface added.

And the 1920s?

If the 1940s and 1950s haven’t sparked enough curiosity, another mystery survives from the 1920s.

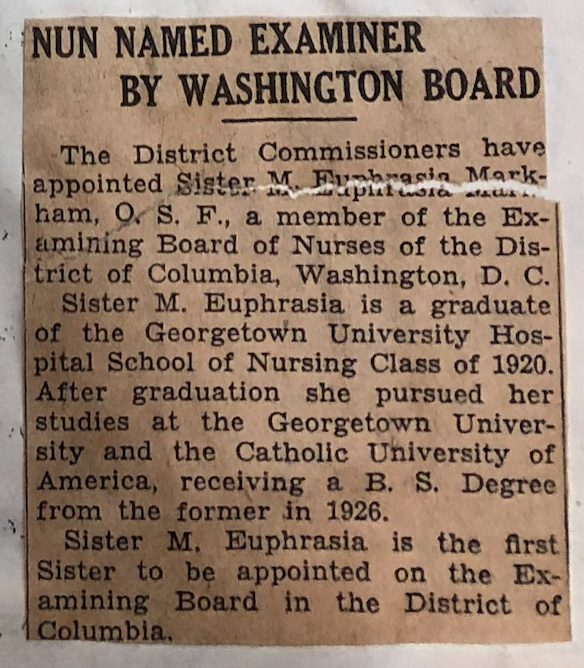

An unsourced news article, likely from 1930, noted that Sister M. Euphrasia Markham, O.S.F., earned, at Georgetown, a diploma in nursing in 1920 and a bachelor’s degree in 1926. (Photo of clip housed in the Georgetown University Archives.)

Specifically, how did two members of the Sisters of Saint Francis, Sister Mary Euphrasia Markam and Sister Joanilla Knott, end up earning their bachelor’s degrees in nursing at Georgetown in the mid-20s?

The first, Sister Mary Euphrasia received both her diploma and baccalaureate in nursing at Georgetown. She led the nursing school and garnered a John Carroll Award in 1957, the first woman to do so, according to the Alumni Association, which has described this puzzle on its website. (Read the story.)

“Sister Mary Euphrasia may also hold a distinctive place in Georgetown history as the first woman to graduate from Georgetown University,” the association noted, hypothesizing she may have received individual tutoring to earn the degree.

Documents recently made available by the archives of the Sisters of Saint Francis in Philadelphia helped corroborate the association’s account: Sister Mary Euphrasia, who died in 1973, received, at Georgetown, the diploma in 1920 and the B.S. in nursing in 1926.

An unsourced news article in the Georgetown Archives shared that Sister M. Euphrasia Markham would be serving on the DC Nurses’ Examining Board. She “is a graduate of the Georgetown University Hospital School of Nursing Class of 1920. After graduation she pursued studies at the Georgetown University and the Catholic University of America, receiving a B. S. Degree from the former in 1926,” the article, likely from 1930, announced.

Additionally, an advertisement for Georgetown University and its various schools that appeared in the Sunday Star on September 4, 1932 listed her as “Sr. Euphrasia, O. S. F., R. N., B. S., Superintendent.”

Sister Mary Euphrasia Markham, OSF (Courtesy Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia Archives in Aston, Pennsylvania.)

Sister Joanilla, like Sister Mary Euphrasia, is listed as having received her bachelor’s degree in nursing in 1926 within the 1957 alumni directory. She also, as mentioned previously, led the nursing school for a time and earned her diploma in nursing on campus, likely, although sources vary, in 1916.

Sister Joanilla, according to obituaries and other materials provided by the Sisters of Saint Francis, died in 1960. Those documents do not list a graduation year, although they do say she completed her bachelor’s at Georgetown.

Perhaps she and Sister Mary Euphrasia are to be considered the first women Georgetown grads.

That said, complicating this mystery, neither woman is listed in Georgetown’s 1926 Commencement program. Further, an unsigned letter from 1925 (cited by Woolley and reviewed in the Georgetown Archives) – likely from President Charles W. Lyons, SJ, and written to Sister Rodriguez, OSF, the nursing school’s superintendent – dismissed the idea of a baccalaureate degree in nursing.

~~~

Most definitely, this feature story just scratches the surface. As the celebration of the College’s significant anniversary of admitting women occurs this academic year, a closer look at the achievements, policies, and practices related to earlier nursing students is worthwhile.

More Reading

Dr. Robert Emmett Curran’s three-volume history, A History of Georgetown University, particularly sections of volumes two and three and his listing of academic and administrative officers of the university. Citing Woolley, Curran called the extension courses “a pilot program of sorts.”

Abigail Eastman, “‘Women Pioneers’ Shape Hilltop for Over 50 Years,” the Hoya, March 22, 2019.

Sister Angela Maria, SCN, and Dr. Elizabeth Reichert Smith’s essay, “Half-Century Survey,” which appeared in the May 1958 issue of the Georgetown University Alumni Magazine

Rose A. McGarrity’s 1975 unpublished manuscript, edited by Dr. Rita Marie Bergeron, “From Apprenticeship to Professionalism: A Brief History of the Georgetown University School of Nursing 1903-1975”

Father Lawrence C. McHugh’s paper, “The Development of the Georgetown University School of Nursing,” offered as a part of the 175th celebration of Georgetown’s founding on March 20, 1964

Dr. Susan L. Poulson’s 1989 Georgetown dissertation, “A Quiet Revolution”: The Transition to Coeducation at Georgetown and Rutgers Colleges, 1960-1975. Poulson’s work offers helpful context about the history of coeducation with respect to Catholicism and the Jesuits, the coeducational makeup of Georgetown’s other schools before the College’s “momentous decision” to become coed, and changes in culture on the Hilltop.

Dr. Alma S. Woolley’s 2001 history, Learning, Faith, and Caring: History of the Georgetown University School of Nursing, 1903-2000. Woolley wrote, “The university’s decision in 1968 to admit women to the college in fall 1969 is considered its transition to coeducation, and is cited as the date when women came to campus. The fact that nursing students had been on campus since 1903, and the other three undergraduate schools all had admitted women earlier, has not changed this perception.”

Nota Bene

This ongoing project is a collaboration between Bill Cessato at the School of Nursing & Health Studies and Lynn Conway and Ann Galloway at the University Archives. Cessato authored this feature article. A very special thank you goes to HelenMarie Dolton, whose record-keeping for many decades started this meaningful endeavor. Dolton generously spent a great deal of her own time mailing copies and emailing photos of documents, as well as providing insights. This article would have not been possible without her. If graduates wish to share related memories, they may do so at nhscommunications@georgetown.edu.

- Tagged

- Nursing History