BSN Alumna of the Class of 1954 Discusses Time as Georgetown Student

January 21, 2021 – When Anne (Sherer) Jackson’s mother dropped her off on campus to begin the five-year BSN Program in 1949, she was terrified.

“I was just scared to death because it was still an all-boys school, and I had just come from an all-girls high school,” she said. “And I remember my mother letting me off on the first day. I think there was a gate over there by White-Gravenor. And then I went and I spent most of my student first year in the girl’s sitting room when I wasn’t in class.”

During the onetime five-year degree program, nursing students went through two years of study in the College of Arts and Sciences and then did three years in the School of Nursing.

“We took the usual classes the boys did, which I think was two years of pre-med,” she said. “And the whole first year I spent most the time grumbling about college, and my mother said, ‘If you don’t like it, quit.’ Well, that was a challenge, so I stayed on, and I finished my full five years.”

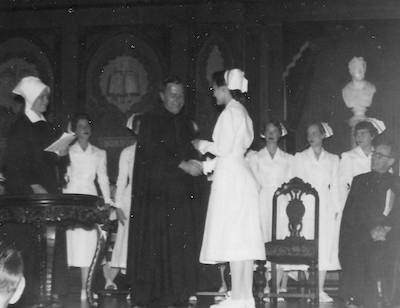

According to Dr. Alma Woolley’s Learning, Faith, and Caring: History of the Georgetown University School of Nursing, 1903-2000, Father McHugh, during March of 1954, recommended to Father Bunn the idea of a special awards ceremony in Gaston Hall for nursing graduates similar to Tropaia. The above photo is likely from that event.

College Courses

Jackson said that during the College years she took various courses, including with the male students on the campus. She remembered classes in chemistry, English, ethics, European history covering the period 1500-1812, French, and zoology.

She added that the men were, at that time, required to were to class a coat and a tie, while she and her nursing classmates usually wore dresses or skirts and blouses – never blue jeans, which were not permitted.

“The [boys] I knew were nice, they never seemed to object to us,” she said. “. . . The ones I knew were all very nice – never been any mention that they resented the girls on campus.”

Remembering Dr. Hufnagel

After their College coursework, the women began their nursing studies, taking nursing arts and other subjects. Jackson indicated the nursing education was “very thorough,” but said she wished she had learned a few techniques, like drawing blood and listening to heart and lung sounds, that would have been helpful later in her nursing career.

She also said a member of the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth, who were administrators at the hospital and nursing school at this time, was “always the supervisor on the hall you worked on.”

Additionally, she highlighted the pioneering work of Dr. Charles Hufnagel, who implanted his heart valve in a patient at Georgetown in 1952. “He was a very, very nice man,” she said. “Whoever took care of one of his patients, he wanted to talk to them, not the head nurse who was covering.” (Learn more about Dr. Hufnagel.)

Jackson added: “And the first transplant was a ball-and-socket thing. And when you got off the elevator at the hospital, you could hear, ‘click, click, click,’ because that little ball would rise up and then fall back down after the contractions stopped. . . . We were not allowed to talk to anybody, especially reporters or anything like that.”

“He was as nice to his students or an aide or anybody as he was to anybody in the hospital,” she said. “He was just a very nice man.”

In their senior year, Jackson said, students did their clinical affiliations, at sites other than Georgetown’s hospital, in pediatric, psychiatric, and tubercular nursing. These lasted between six weeks and three months.

Visiting Nurses

Clinical education, she said, also included two months with the visiting nurse association, through which, “We were all given a certain area in Washington. . . . We made our rounds on the buses and visited patients in their home.”

Later, in the interview, she remembered being treated with kindness wherever she went as a visiting nurse. She described how students wore a different style of uniform and cap while they did this work in the community.

“We’d wear a blue dress,” she said. “And then we had a dark blue coat and then this cap that looked like the kind that Army privates wear. . . . And we had a black bag, which carried our medical needs for patients.” She noted, for example, bandages and syringes.

“. . . You would go into the office in the morning, and you would get your list of patients to go and visit,” she recalled. “And then you took buses, and either gave them the shots or sat and changed a bandage or something like that.”

Inside her bag, Jackson carried a blood pressure cuff. “. . . You pumped [the patients’] arm up until you quit hearing any sound,” she said. “And the first sound you heard was the systolic rating. And then when it went away, it was the diastolic rating.”

During this period of segregation, Jackson said that she remembered visiting a hotel around U Street for Black residents. There, she cared for “a little girl who had to be cleared of being over the chickenpox.”

In another home on her rounds, a five-year-old child told the young nursing student, “‘When I grow up, I’m going to be a nurse.’” Then the child, hoping to buy some gum, asked for a nickel.

Dorm Life

Jackson, who grew up in Arlington, did not live on campus in the two College years, but she did live on the third floor for two years in the original hospital complex between 35th and 36th Streets. During their final year, the 10 students lived in rooms on the fifth floor that had been used by the sisters.

“I didn’t move on campus until I started the clinical part,” she said. “I day hopped for two years, and so I missed out on some of the stuff in the dorm. But after three years, one of the girls and I decided we’d like to be roommates. . . . We had a good time. We were supposed to be in bed by 10, and the elevator, we could hear it coming. We all got into bed real quick, because sister used to make rounds and you had to be in bed by 10.”

She noted, “. . . Our rooms were on either side of the chapel because the 10 of us could all live up there. We had a little room, and we had a ball up there.”

Occasionally, the students were required to do retreats and were given meditations to reflect upon by one of the Jesuit priests. Jackson shared two humorous stories, one involving a friend getting into trouble with one of the sisters for sitting on the bunkbed – in a green hat turned sideways – using cards to tell fortunes.

Another time, the students trapped a napping classmate in her hospital-style bed. “We cranked the foot all the way up and the head all the way up, so she was caught in the mattress, and we heard the elevator coming. So, we didn’t do a lot of meditating on occasion. But we had so much fun.”

‘Didn’t Want to Leave’

Across Prospect Street sits a beautiful brick home, Jackson recalled. “We had a corner room, and once they had a marvelous party, and we hung out the windows and looked at the guests coming and all this wonderful food. We were going to see if we could try and sneak in.”

Curfew was 10 PM during the week, and students could twice request, each month, permission for an 11 PM extension, as well as – with a parental note – one overnight to visit home or a friend’s house.

She said she and her classmates received their nursing caps and uniform bib at the capping ceremony in the hospital chapel – “big things when you’re at that age.” The sister lit a candle the students carried as they were capped, Jackson said.

On June 7, they graduated with the rest of the university’s Class of 1954.

Spotlighting a major change from her frightened feeling that first day of college when her mother dropped her off at White-Gravenor, Jackson said, “. . . My memories of Georgetown are very fond. And when it came time to graduate, of course, then I didn’t want to leave – thoroughly enjoyed it.”

By Bill Cessato

The author thanks Mrs. Jackson for mailing and e-mailing photographs, as well as her time reviewing and editing the article draft.

- Tagged

- Nursing History